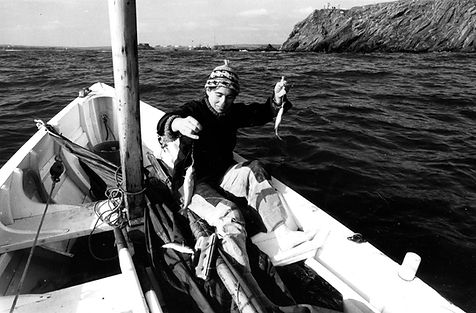

Sally Seymour, my mother

“How do you feel?” “So sorry for your loss” “She was a great woman, so creative - influenced so many” Friends look at me with concern and kindness.

How do I feel? Truth is, I don’t know. People are so kind, but they are doing the feeling for me right now. In true Seymour style I am just getting on with it!

“You will be able to remember her as she was before her stroke,” my cousin said. But who was she then? Well, she was extraordinary then, of course…

Firstly smallholding, then her artistic career, were her life’s work – her reason to exist. She brought her, and my father’s vision to life, eventually adopting it as her own. She had been brought up in an atmosphere of self-reliance, as her mother had been a determinedly resourceful and accomplished woman, and her life was just an extension of her childhood. My mother’s ambition was to be able to do everything to a good standard, be it woodwork, cement work, brick or stone wall building, making pig houses and chicken houses. She tried carving, painting, plastering, fencing, ploughing, all small veg and large crop growing, animal husbandry, playing vet, doctor, midwife. She set bones and delivered many a baby animal, and at least one human one. She eased animals into our world and nurtured them with calculated ruthlessness until they could manage - she wasn’t afraid of the realities of life and death. She would cure animal skins, shear her own sheep, dye, spin and knit and weave and felt and crochet. She made cloth from nettle fibres, and grew flax for linen. She made baskets, and hurdles and planted living willow barriers. She made butter, and cheese, and yoghurt, and bacon, and ham, and caught and salted fish. She salted and froze and bottled vegetables, made wine and beer and bread, kept bees for honey. She cooked good, healthy meals, using food that she grew, and the animal products she processed. She kept the fires alight. And she became a successful potter, book illustrator and painter. She was greedy for the next challenge, insatiable for accomplishment – always spurred on by necessity due to the mind - numbing lack of money. She wouldn’t dream of asking someone else to make what we needed, or to buy from a shop.

My childhood years marched to the rhythm of her activities: to the scritch scritch scratch of her hoe, the chop chop chop of her vegetable knife, the click click clack of her needles. Every movement was an expression of her mood. She did not verbalise her feelings. She knitted them into her hand spun jumpers, thumped them into her clay - kneaded them into her bread. She wore her disappointment like a mantle, which she drew jealously around herself to keep us out. Her grief was private.

My mother was beautiful, and could shine in company. She responded to admiration, and was loved and admired by our father without reserve. She would sing at evening gatherings if encouraged. My father kept order for her, but there was no need, her clear voice would sweep away the chatter as it rose up. I would watch as he listened adoringly to the haunting clarity of her voice.

Every minute of every day was taken up in useful production, right into the corners. She moved from job to job with purposeful, efficient, easy grace. I would follow her like a small sprite – a self-appointed guardian angel, but at some time when my attention had wandered, she would give me the slip. Then I’d look for her, all over the farm, searching in all the places she might be. She could be anywhere; counting the sheep, fixing a fence, milking the cow, in the pottery, the garden planting out lettuce seedlings, or in the top shed scraping an animal skin as it cures. Or simply drawing quietly somewhere, beautifully representing our life on paper. But not with me. The ethos of our family was self-reliance, and I was taught to fall back on my own resources early.

The soft mother who I longed for, someone well covered and comfortable – someone who laughed a lot, put her work aside for a while just to spend time with me, who gave me constant guidance and encouragement, was not Sally. She was far too busy to be much interested in what we were up to for most of the time.

My mother showed by example how to run a smallholding. Admired for her steady capabilities, she was inspiration for many an aspiring smallholder, who went on their way secure in the knowledge that it could be done. But she was happier to be free of the weight of people all around her, she was not sociable, or chatty, and preferred her own company. She wanted to work on her own, and if someone insisted on hanging around, she would give them a job other than the one that she was doing. She tackled everything with non-verbal quiet determination. Communicating her achievements came after the act of performing them. Life for her was conditional. You were judged by your efforts and your skill. People to her were mostly not just for company, that she did not want much, in fact she went out of her way to avoid it. They had to be useful.

Love was the hand-spun knitted gloves she made for you, or the dragon she painted on your bedroom wall, or the pottery chicken lid sitting on a pot filled with currants. Her need for recognition and approval was unquenchable, and love for herself was asked for only after the completion of a project, proudly presented to be admired - the love being returned by the admiration given. It depended on what you could achieve, how good are you at what you do? “How can you be useful to my world? - Can I admire you - do you shape up?”.

And then she had a stroke, and in one devastating moment it all changed.

I have often wondered why, being stuck in the mindset of; ‘All things happen for a reason’. We looked after her broken body for 21 years, we ‘Just got on with it!’ But often in some moments, when the going was tough, I struggled for the reason.

Looking at an old photograph - so bright and determined, stubborn and indomitable - and so strong and beautiful, I could only wonder at the change. She was the same woman but different - the dichotomy puzzled me daily, and yet in physiological terms it was easy to explain. Her brain and body were damaged from oxygen deprivation caused by the stroke, parts of the brain which control the body were broken beyond repair.

Now it seemed all about damage limitation. Her whole world was as small as the daily maintenance of her remaining faculties, and apart from the memory of her previous persona, which fluttered around her like a dream, she was someone else. She watched the family march along without her involvement, her only effect on us was how we all related to and coped with her day to day, year to year methods of managing her new body. All her busyness was used up.

But it was so much more than that. If there was a reason at all for those years of struggle and frustration, it was for her to learn to just be…and to love without the hinderance of life’s constant interference. And she did. There was warmth and empathy, wordless encouragement for my efforts and the achievement of the other members of the family, just pure love.

So how do I feel?

After her small family burial, which went beautifully after a lot of imponderables and some stress, there was Theatre performance, which I wanted to do. Keeping punters happy in the homestay. Then a couple of wwoofers to stay, who needed guidance and attention for a week. Then the Open Studio to prepare for, and importantly, a proper memorial for Sally, which just had to be done. She couldn’t just disappear into obscurity…people were asking to be part of it. An endless list of jobs, and planning and organising. Worrying about the weather, who was going to talk at the sendoff, beds to be allocated, who of the family could come and when. How many people were likely to come, and would there be enough cake? Along with sorting out death certificates, informing the right authorities, telling people of her death…

As David and I rushed from job to job wondering when we would break, I slowly became aware that the weather was beautiful, and there developed in me a huge sense of gratitude. I stood with the sun on my back and watched the wind rustle in the trees. Sally loved the warmth of the sun. She loved the early morning dew, bird song, the beauty in flowers and trees. I sat by her grave and a pigeon in a nearby tree gave voice, a buzzard flew overhead. Bees buzzed, and a butterfly wended its way. I had a sense of her presence in all elemental things. She was there, I realised, in the flowers, the birds and insects, and the wind in the trees. Her energy had exploded into the life force around me. From then on she was with me at all stages of my work, watching and encouraging and helping. Giving me strength. All of the things I imagined were lacking in my childhood she gave to me a thousand fold.

But mostly to me came the realisation that she was free. I don’t know how I will feel tomorrow or in a week. Sad, probably, I will miss her, I will remember and appreciate all those little things and regret that I didn’t tell her at the time. But she knew we loved her.

And as for a reason for anything…well that is probably my fabrication. Life is random, it is wonderful, and it is achingly terrible at times. Things happen beyond our control, and it all just goes on. I don’t know how I will feel in a week, a year, but at that moment I felt overwhelming happiness.